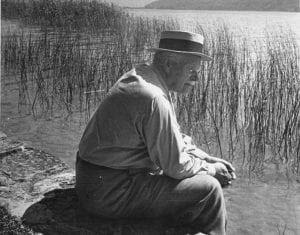

Life is never so beautiful as when surrounded by death. ~Carl Jung, Seminar 1925, Page 85

Carl Jung on “Death and Fate” - Anthology

What is it, in the end, that induces a man to go his own way and to rise out of unconscious identity with the mass as out of a swathing mist?

Not necessity, for necessity comes to many, and they all take refuge in convention.

Not moral decision, for nine times out of ten we decide for convention likewise.

What is it, then, that inexorably tips the scales in favour of the extra-ordinary

It is what is commonly called vocation: an irrational factor that destines a man to emancipate himself from the herd and from its well-worn paths.

True personality is always a vocation and puts its trust in it as in God, despite its being, as the ordinary man would say, only a personal feeling.

But vocation acts like a law of God from which there is no escape.

The fact that many a man who goes his own way ends in ruin means nothing to one who has a vocation.

He must obey his own law, as if it were a daemon whispering to him of new and wonderful paths.

Anyone with a vocation hears the voice of the inner man: he is called. ~Carl Jung, CW 17, Para 299

Much indeed can be attained by the will, but, in view of the fate of certain markedly strong-willed personalities, it is a fundamental error to try to subject our own fate at all costs to our will.

Our will is a function regulated by reflection; hence it is dependent on the quality of that reflection.

This, if it really is reflection, is supposed to be rational, i.e., in accord with reason.

But has it ever been shown, or will it ever be, that life and fate are in accord with reason, that they too are rational?

We have on the contrary good grounds for supposing that they are irrational, or rather that in the last resort they are grounded beyond human reason. io4a:72

We cannot rate reason highly enough, but there are times when we must ask ourselves: do we really know enough about the destinies of individuals to entitle us to give good advice under all circumstances?

Certainly we must act according to our best convictions, but are we so sure that our convictions are for the best as regards the other person?

Very often we do not know what is best for ourselves, and in later years we may occasionally thank God from the bottom of our hearts that his kindly hand has preserved us from the "reasonableness" of our former plans.

It is easy for the critic to say after the event, "Ah, but then it wasn't the right sort of reason!"

Who can know with unassailable certainty when he has the right sort?

Moreover, is it not essential to the true art of living, sometimes, in defiance of all reason and fitness, to include the unreasonable and the unfitting within the ambiance of the possible? ~Carl Jung, CW 16, Para 462

Reason must always seek the solution in some rational, consistent, logical way, which is certainly justifiable enough in all normal situations but is entirely inadequate when it comes to the really great and decisive questions.

It is incapable of creating the symbol because the symbol is irrational.

When the rational way proves to be a cul de sac—as it always does after a time—the solution comes from the side it was least expected. 69:438

We distinctly resent the idea of invisible and arbitrary forces, for it is not so long ago that we made our escape from that frightening world of dreams and superstitions, and constructed for ourselves a picture of the cosmos worthy of our rational consciousness—that latest and greatest achievement of man.

We are now surrounded by a world that is obedient to rational laws.

It is true that we do not know the causes of everything, but in time they will be discovered, and these discoveries will accord with our reasoned expectations.

There are, to be sure, also chance occurrences, but they are merely accidental, and we do not doubt that they have a causality of their own.

Chance happenings are repellent to the mind that loves order.

They disturb the regular, predictable course of events in the most absurd and irritating way.

We resent them as much as we resent invisible, arbitrary forces, for they remind us too much of Satanic imps or of the caprice of a deus ex machina.

They are the worst enemies of our careful calculations and a continual threat to all our undertakings.

Being admittedly contrary to reason, they deserve all our abuse, and yet we should not fail to give them their due. ~Carl Jung, CW 10, Para 113

What if there were a living agency beyond our everyday human world—something even more purposeful than electrons ?

Do we delude ourselves in thinking that we possess and control our own psyches, and is what science calls the "psyche" not just a question-mark arbitrarily confined within the skull, but rather a door that opens upon the human world from a world beyond, allowing unknown and mysterious powers to act upon man and carry him on the wings of the night to a more than personal destiny. ~Carl Jung, CW 15, Para 148

"The stars of thine own fate lie in thy breast," says Seni to Wallenstein—a dictum that should satisfy all astrologers if we knew even a little about the secrets of the heart.

But for this, so far, men have had little understanding.

Nor would I dare to assert that things are any better today. ~Carl Jung, CW 10, Para 9

Whether primitive or not, mankind always stands on the brink of actions it performs itself but does not control.

The whole world wants peace and the whole world prepares for war, to take but one example.

Mankind is powerless against mankind, and the gods, as ever, show it the ways of fate.

Today we call the gods "factors," which comes from facere, 'to make.'

The makers stand behind the wings of the world-theatre.

It is so in great things as in small.

In the realm of consciousness we are our own masters; we seem to be the "factors" themselves.

But if we step through the door of the shadow we discover with terror that we are the objects of unseen factors, 10:49

It is dangerous to avow spiritual poverty, for the poor man has desires, and whoever has desires calls down some fatality on himself.

A Swiss proverb puts it drastically: "Behind every rich man stands a devil, and behind every poor man two." ~Carl Jung, CW 10, Para 28

In our strength we are independent and isolated, and are masters of our own fate; in our weakness we are dependent and bound, and become unwilling instruments of fate, for here it is not the individual will that counts but the will of the species. 114:261

Without wishing it, we human beings are placed in situations in which the great "principles" entangle us in something, and God leaves it to us to find a way out.

~Carl Jung, CW 18, Para 869

People often behave as if they did not rightly understand what constitutes the destructive character of the creative force.

A woman who gives herself up to passion, particularly under present-day civilized conditions, experiences this all too soon.

We must think a little beyond the framework of purely bourgeois moral conditions to understand the feeling of boundless uncertainty which befalls the man

who gives himself over unconditionally to fate.

Even to be fruitful is to destroy oneself, for with the creation of a new generation the previous generation has passed beyond its climax.

Our off spring thus become our most dangerous enemies, with whom we cannot get even, for they will survive us and so inevitably will take the power out of our weakening hands.

Fear of our erotic fate is quite understandable, for there is something unpredictable about it. ~Carl Jung, CW 5, Para 101

It is not I who create myself, rather I happen to myself. ~Carl Jung, CW 11, Para 391

What happens to a person is characteristic of him.

He represents a pattern and all the pieces fit.

One by one, as his life proceeds, they fall into place according to some predestined design. ~Carl Jung, Men, Women, and God. ~Daily Mail, April 1955.

The reality of good and evil consists in things and situations that just happen to you, that are too big for you, where you are always facing death.

Anything that comes upon me with this intensity I experience as numinous, no matter whether I call it divine or devilish or just "fate." ~Carl Jung, CW 10, Para 871

The great decisions in human life usually have far more to do with the instincts and other mysterious unconscious factors than with conscious will and well-meaning reasonableness.

The shoe that fits one person pinches another; there is no universal recipe for living.

Each of us carries his own life-form within him—an irrational form which no other can outbid. ~Carl Jung, CW 16, Para 81

Fear of fate is a very understandable phenomenon, for it is incalculable, immeasurable, full of unknown dangers.

The perpetual hesitation of the neurotic to launch out into life is readily explained by his desire to stand aside so as not to get involved in the dangerous struggle for existence.

But anyone who refuses to experience life must stifle his desire to live—in other words, he must commit partial suicide. ~Carl Jung, CW 5, Para 165

In the domain of pathology I believe I have observed cases where the tendency of the unconscious would have to be regarded, by all human standards, as essentially destructive.

But it may not be out of place to reflect that the self-destruction of what is hopelessly inefficient or evil can be understood in a higher sense as another attempt at compensation.

There are murderers who feel that their execution is condign punishment, and suicides who go to their death in triumph. ~Carl Jung, CW 14, Para 149

Grounds for an unusually intense fear of death are nowadays not far to seek: they are obvious enough, the more so as all life that is senselessly wasted and misdirected means death too.

This may account for the unnatural intensification of the fear of death in our time, when life has lost its deeper meaning for so many people, forcing them to exchange the life-preserving rhythm of the aeons for the dread ticking of the clock. ~Carl Jung, CW 10, Para 696

In the secret hour of life's midday the parabola is reversed, death is born.

The second half of life does not signify ascent, unfolding, increase, exuberance, but death, since the end is its goal.

The negation of life's fulfilment is synonymous with the refusal to accept its ending.

Both mean not wanting to live, and not wanting to live is identical with not wanting to die.

Waxing and waning make one curve. 90 : 800

Like a projectile flying to its goal, life ends in death.

Even its ascent and its zenith are only steps and means to this goal. 90:803

Death is psychologically as important as birth and, like it, is an integral part of life. ~Carl Jung, CW 13, Para 68

The birth of a human being is pregnant with meaning, why not death?

For twenty years and more the growing man is being prepared for the complete unfolding of his individual nature, why should not the older man prepare

himself twenty years and more for his death? ~Carl Jung, CW 8, Para 803

As a doctor I am convinced that it is hygienic—if I may use the word—to discover in death a goal towards which one can strive, and that shrinking away from it is something unhealthy and abnormal which robs the second half of life of its purpose. ~Carl Jung, CW 8, Para 792

We know of course that when for one reason or another we feel out of sorts, we are liable to commit not only the minor follies, but something really dangerous which, given the right psychological moment, may well put an end to our lives.

The popular saying, "Old so-and-so chose the right time to die," comes from a sure sense of the secret psychological cause. ~Carl Jung, CW 7, Para i94

That the highest summit of life can be expressed through the symbolism of death is a well-known fact, for any growing beyond oneself means death. ~Carl Jung, CW 5, Para 432

The psyche pre-existent to consciousness (e.g., in the child) participates in the maternal psyche on the one hand, while on the other it reaches across to the daughter psyche.

We could therefore say that every mother contains her daughter in herself and every daughter her mother, and that every woman extends backwards into her mother and forwards into her daughter.

This participation and intermingling give rise to that peculiar uncertainty as regards time: a woman lives earlier as a mother, later as a daughter.

The conscious experience of these ties produces the feeling that her life is spread out over generations—the first step towards the immediate experience and conviction of being outside time, which brings with it a feeling of immortality.

The individual's life is elevated into a type, indeed it becomes the archetype of woman's fate in general.

This leads to a restoration or apocatastasis of the lives of her ancestors, who now, through the bridge of the momentary individual, pass down into the generations of the future.

An experience of this kind gives the individual a place and a meaning in the life of the generations, so that all unnecessary obstacles are cleared out of the way of the life stream that is to flow through her.

At the same time the individual is rescued from her isolation and restored to wholeness. ~Carl Jung, CW 9i, Para 316

Our life is indeed the same as it ever was.

At all events, in our sense of the word it is not transitory; for the same physiological and psychological processes that have been man's for hundreds of thousands of years still endure, instilling into our inmost hearts this profound intuition of the "eternal" continuity of the living.

But the self, as an inclusive term that embraces our whole living organism, not only contains the deposit and totality of all past life, but is also a point of departure, the fertile soil from which all future life will spring.

This premonition of futurity is as clearly impressed upon our innermost feelings as is the historical aspect.

The idea of immortality follows legitimately from these psychological premises. ~Carl Jung, CW 7, Para 303

For the man of today the expansion of life and its culmination are plausible goals, but the idea of life after death seems to him questionable or beyond belief.

Life's cessation, that is, death, can only be accepted as a reasonable goal either when existence is so wretched that we are only too glad for it to end, or when we are convinced that the sun

strives to its setting "to illuminate distant races" with the same logical consistency it showed in rising to the zenith.

But to believe has become such a difficult art today that it is beyond the capacity of most people, particularly the educated part of humanity.

They have become too accustomed to the thought that, with regard to immortality and such questions, there are innumerable contradictory opinions

and no convincing proofs.

And since "science" is the catchword that seems to carry the weight of absolute conviction in the temporary world, we ask for "scientific" proofs.

But educated people who can think know very well that proof of this kind is a philosophical impossibility.

We simply cannot know anything whatever about such things. ~Carl Jung, CW 8, Para 790

One should not be deterred by the rather silly objection that nobody knows whether these old universal ideas—God, immortality, freedom of the will, and so on—are "true" or not.

Truth is the wrong criterion here.

One can only ask whether they are helpful or not, whether man is better off and feels his life more complete, more meaningful and more satisfactory with or without them. ~Carl Jung, Face to Face, Pages 48-51

It would all be so much simpler if only we could deny the existence of the psyche.

But here we are with our immediate experiences of something that is—something that has taken root in the midst of our measurable, ponderable, three dimensional reality, that differs mysteriously from this in every respect and in all its parts, and yet reflects it.

The psyche could be regarded as a mathematical point and at the same time as a universe of fixed stars.

It is small wonder, then, if, to the unsophisticated mind, such a paradoxical being borders on the divine.

If it occupies no space, it has no body.

Bodies die, but can something invisible and incorporeal disappear?

What is more, life and psyche existed for me before I could say "I," and when this "I" disappears, as in sleep or unconsciousness, life and psyche still go on, as our observation of other people and our own dreams inform us.

Why should the simple mind deny, in the face of such experiences, that the "soul" lives in a realm beyond the body? ~Carl Jung, CW 8, Para 671

Everything psychic is pregnant with the future. ~Carl Jung, CW 14, Para 53

The cult of the dead is rationally based on the belief in the supra-temporality of the soul, but its irrational basis is to be found in the psychological need of the living to do something for the departed.

This is an elementary need which forces itself upon even the most "enlightened" individuals when faced by the death of relatives and friends.

That is why, enlightenment or no enlightenment, we still have all manner of ceremonies for the dead.

If Lenin had to submit to being embalmed and put on show in a sumptuous mausoleum like an Egyptian pharaoh, we may be quite sure it was not because his followers believed in the resurrection of the body.

Apart, however, from the Masses said for the soul in the Catholic Church, the provisions we make for the dead are rudimentary and on the lowest level, not because we cannot convince ourselves of the soul's immortality, but because we have rationalized the abovementioned psychological need out of existence.

We behave as if we did not have this need, and because we cannot believe in a life after death we prefer to do nothing about it.

Simpler-minded people follow their own feelings, and, as in Italy, build themselves funeral monuments of gruesome beauty.

The Catholic Masses for the soul are on a level considerably above this, because they are expressly intended for the psychic welfare of the deceased and are not a mere gratification of lachrymose sentiments. ~Carl Jung, CW 11, Para 855

Flight from life does not exempt us from the laws of old age and death.

The neurotic who tries to wriggle out of the necessity of living wins nothing and only burdens himself with a constant foretaste of aging and dying, which must appear especially cruel on account of the total emptiness and meaninglessness of his life.

If it is not possible for the libido to strive forwards, to lead a life that willingly accepts all dangers and ultimate decay, then it strikes back along the other road and sinks into its own depths, working down to the old intimation of the immortality of all that lives, to the old longing for rebirth. ~Carl Jung, CW 5, Para 617

The sun, rising triumphant, tears himself from the enveloping womb of the sea, and leaving behind him the noonday zenith and all its glorious works, sinks down again into the maternal depths, into all-enfolding and all regenerating night.

This image is undoubtedly a primordial one, and there was profound justification for its becoming a symbolical expression of human fate: in the morning

of life the son tears himself loose from the mother, from the domestic hearth, to rise through battle to his destined heights.

Always he imagines his worst enemy in front of him, yet he carries the enemy within himself—a deadly longing for the abyss, a longing to drown in his own

source, to be sucked down to the realm of the Mothers.

His life is a constant struggle against extinction, a violent yet fleeting deliverance from ever-lurking night.

This death is no external enemy, it is his own inner longing for the stillness and profound peace of all-knowing non-existence, for all-seeing sleep in the ocean of coming-to-be and passing away.

Even in his highest strivings for harmony and balance, for the profundities of philosophy and the raptures of the artist, he seeks death, immobility, satiety, rest.

If, like Peirithous, he tarries too long in this abode of rest and peace, he is overcome by apathy, and the poison of the serpent paralyses him for all time.

If he is to live, he must fight and sacrifice his longing for the past in order to rise to his own heights.

And having reached the noonday heights, he must sacrifice his love for his own achievement, for he may not loiter.

The sun, too, sacrifices its greatest strength in order to hasten onward to the fruits of autumn, which are the seeds of rebirth. ~Carl Jung, CW 5, Para 553

Only that which can destroy itself is truly alive. ~Carl Jung, CW 12, Para 93

The highest value, which gives life and meaning, has got lost.

This is a typical experience that has been repeated many times, and its expression therefore occupies a central place in the Christian mystery.

The death or loss must always repeat itself: Christ always dies, and always he is born: for the psychic life of the archetype is timeless in comparison with our individual time-boundness.

According to what laws now one and now another aspect of the archetype enters into active manifestation, I do not know.

I only know—and here I am expressing what countless other people know—that the present is a time of God's death and disappearance.

The myth says he was not to be found where his body was laid. "Body" means the outward, visible form, the erstwhile but ephemeral setting for the highest

value.

The myth further says that the value rose again in a miraculous manner, transformed. ~Carl Jung, CW 11, Para 149

The three days' descent into hell during death describes the sinking of the vanished value into the unconscious, where, by conquering the power of darkness, it establishes a new order, and then rises up to heaven again, that is, attains supreme clarity of consciousness.

The fact that only a few people see the Risen One means that no small difficulties stand in the way of finding and recognizing the transformed value. ~Carl Jung, CW 11, Para 149

When the libido leaves the bright upper world, whether from choice, or from inertia, or from fate, it sinks back into its own depths, into the source from which it originally flowed, and returns to the point of cleavage, the navel, where it first entered the body.

This point of cleavage is called the mother, because from her the current of life reached us.

Whenever some great work is to be accomplished, before which a man recoils, doubtful of his strength, his libido streams back to the fountainhead—and

that is the dangerous moment when the issue hangs between annihilation and new life.

For if the libido gets stuck in the wonderland of this inner world, then for the upper world man is nothing but a shadow, he is already moribund or at least seriously ill.

But if the libido manages to tear itself loose and force its way up again, something like a miracle happens: the journey to the underworld was a plunge into the fountain of youth, and the libido, apparently dead, wakes to renewed fruitfulness. ~Carl Jung, CW 5, Para 449

The birth of a saviour is equivalent to a great catastrophe, because a new and powerful life springs up just where there had seemed to be no life and no power and no possibility of further development.

It comes streaming out of the unconscious, from that unknown part of the psyche which is treated as nothing by all rationalists.

From this discredited and rejected region comes the new afflux of energy, the renewal of life.

But what is this discredited and rejected source of vitality?

It consists of all those psychic contents that were repressed because of their incompatibility with conscious values—everything hateful, immoral, wrong, unsuitable, useless, etc., which means everything that at one time or another appeared so to the individual concerned.

The danger is that when these things reappear in a new and wonderful guise, they may make such an impact on him that he will forget or repudiate all his former values.

What he once despised now becomes the supreme principle, and what was once truth now becomes error.

This reversal of values amounts to the destruction of the old ones and is similar to the devastation of a country by floods. ~Carl Jung, CW 6, Para 449

If the old were not ripe for death, nothing new would appear; and if the old were not blocking the way for the new, it could not and need not be rooted out. ~Carl ung, CW 6, Para 446

Everything old in our unconscious hints at something coming. ~Carl Jung, CW 6, Para 630

The mere fact that people talk about rebirth, and that there is such a concept at all, means that a store of psychic experiences designated by that term must actually exist.

What these experiences are like we can only infer from the statements that have been made about them.

So, if we want to find out what rebirth really is, we must turn to history in order to ascertain what "rebirth" has been understood to mean. ~Carl Jung, CW 9i, Para 206

Rebirth is an affirmation that must be counted among the primordial affirmations of mankind. ~Carl Jung, CW 9i, Para 207

In the initiation of the living, "Beyond" is not a world beyond death, but a reversal of the mind's intentions and outlook, a psychological "Beyond" or, in Christian terms, a "redemption" from the trammels of the world and of sin.

Redemption is a separation and deliverance from an earlier condition of darkness and unconsciousness, and leads to a condition of illumination and releasedness, to victory and transcendence over everything "given." ~Carl Jung, CW 11, Para 841

We are so hemmed in by things which jostle and oppress that we never get a chance, in the midst of all these "given" things, to wonder by whom they are "given." ~Carl Jung, CW 11, Para 841

A great reversal of standpoint, calling for much sacrifice, is needed before we can see the world as "given" by the very nature of the psyche.

It is so much more straightforward, more dramatic, impressive, and therefore more convincing, to see all the things that happen to me than to observe how I make them happen.

Indeed, the animal nature of man makes him resist seeing himself as the maker of his circumstances. ~Carl Jung, CW 11, Para 841

If I know and admit that I am giving myself, forgoing myself, and do not want to be repaid for it, then I have sacrificed my claim, and thus a part of myself.

Consequently, all absolute giving, a giving which is a total loss from the start, is a self-sacrifice.

Ordinary giving for which no return is received is felt as a loss; but a sacrifice is meant to be like a loss, so that one may be sure that the egoistic claim

no longer exists.

Therefore the gift should be given as if it were being destroyed.

But since the gift represents myself, I have in that case destroyed myself, given myself away without expectation of return.

Yet, looked at in another way, this intentional loss is also a gain, for if you can give yourself it proves that you possess yourself.

Nobody can give what he has not got. ~Carl Jung, CW 11, Para 390

From that sacrifice we gain ourselves—our "self"—for we have only what we give. ~Carl Jung, CW 11, Para 398

Fear of self-sacrifice lurks deep in every ego, and this fear is often only the precariously controlled demand of the unconscious forces to burst out in full strength.

No one who strives for selfhood (individuation) is spared this dangerous passage, for that which is feared also belongs to the wholeness of the self—the sub-human, or supra-human, world of psychic "dominants" from which the ego originally emancipated itself with enormous effort, and then only partially,

for the sake of a more or less illusory freedom.

This liberation is certainly a very necessary and very heroic undertaking, but it represents nothing final: it is merely the creation of a subject, who, in order to find fulfilment, has still to be confronted by an object.

This, at first sight, would appear to be the world, which is swelled out with projections for that very purpose.

Here we seek and find our difficulties, here we seek and find our enemy, here we seek and find what is dear and precious to us; and it is comforting

to know that all evil and all good is to be found out there, in the visible object, where it can be conquered, punished, destroyed, or enjoyed.

But nature herself does not allow this paradisal state of innocence to continue forever.

There are, and always have been, those who cannot help but see that the world and its experiences are in the nature of a symbol, and that it really reflects something that lies hidden in the subject himself, in his own transubjective reality. ~Carl Jung, CW 11, Para 849

The effect of the unconscious images has something fateful about it. Perhaps—who knows—these eternal images are what men mean by fate. ~Carl Jung, CW 7, Para 183

If the demand for self-knowledge is willed by fate and is refused, this negative attitude may end in real death.

The demand would not have come to this person had he still been able to strike out on some promising by-path.

But he is caught in a blind alley from which only self-knowledge can extricate him.

If he refuses this then no other way is open to him.

Usually he is not conscious of his situation, either, and the more unconscious he is the more he is at the mercy of unforeseen dangers: he cannot get out of the

way of a car quickly enough, in climbing a mountain he misses his foothold somewhere, out skiing he thinks he can negotiate a tricky slope, and in an illness he suddenly loses the courage to live.

The unconscious has a thousand ways of snuffing out a meaningless existence with surprising swiftness. ~Carl Jung, CW 14, Para 675

Consciousness is always only a part of the psyche and therefore never capable of psychic wholeness: for that the indefinite extension of the unconscious is needed.

But the unconscious can neither be caught with clever formulas nor exorcized by means of scientific dogmas, for something of destiny clings to it—indeed, it is sometimes destiny itself. ~Carl Jung, CW 11, Para 906

The new thing prepared by fate seldom or never comes up to conscious expectations.

And still more remarkable though the new thing goes against deeply rooted instincts as we have known them, it is a strangely appropriate expression

of the total personality, an expression which one could not imagine in a more complete form. ~Carl Jung, CW 13, Para 19

If you sum up what people tell you about their experiences, you can formulate it this way: They came to themselves, they could accept themselves, they were able to become reconciled to themselves, and thus were reconciled to adverse circumstances and events.

This is almost like what used to be expressed by saying: He has made his peace with God, he has sacrificed his own will, he has submitted himself to the will of God. ~Carl Jung, CW 11, Para 138

When I examined the course of development in patients who quietly, and as if unconsciously, outgrew themselves, I saw that their fates had something in common.

The new thing came to them from obscure possibilities either outside or inside themselves; they accepted it and grew with its help.

It seemed to me typical that some took the new thing from outside themselves, others from inside; or rather, that it grew into some persons from without, and into others from within.

But the new thing never came exclusively either from within or from without.

If it came from outside, it became a profound inner experience; if it came from inside, it became an outer happening.

In no case was it conjured into existence intentionally or by conscious willing, but rather seemed to be borne along on the stream of time. ~Carl Jung, CW 13, Para 18

I try to accept life and death. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 546-547

Where I find myself unwilling to accept the one or the other [Life or Death] I should question myself as to my personal motives. . . . ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 546-547

Is it the divine will? Or is it the wish of the human heart which shrinks from the Void of death? ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 546-547

In ultimate situations of life and death complete understanding and insight are of paramount importance, as it is indispensable for our decision to go or to stay and let go or to let stay. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 546-547

One needs death to be able to harvest the fruit. Without death, life would be meaningess, since the long-lasting rises again and denies its own meaning. To be, and to enjoy your being, you need death, and limitation enables you to fulfill your being. ~Carl Jung, The Red Book, Page 275.

If I accept death, then my tree greens, since dying increases life. If I plunge into the death encompassing the world, then my buds break open. How much our life needs death! ~Carl Jung, The Red Book, Page 275.

We need the coldness of death to see clearly. Life wants to live and to die, to begin and to end. ~Carl Jung, The Red Book, Page 275.

The moon is dead. Your soul went to the moon, to the preserver of souls. Thus the soul moved toward death. I went into the inner death and saw that outer dying is better than inner death. And I decided to die outside and to live within. For that reason I turned away and sought the place of the inner life. ~Carl Jung, The Red Book, Page 267.

Joy at the smallest things comes to you only when you have accepted death. ~Carl Jung, The Red Book, Page 275.

We cannot slay death, as we have already taken all life from it. If we still want to overcome death, then we must enliven it. Therefore on your journey be sure to take golden cups full of the sweet drink of life, red wine, and give it to dead matter, so that it can win life back. ~Carl Jung; The Red Book; Liber Primus; Page 244.

You must be in the middle of life, surrounded by death on all sides. ~Carl Jung, The Red Book, Page 370.

If I am bound to men and things, I can neither go on with my life to its destination nor can I arrive at my very own and deepest nature. Nor can death begin in me as a new life, since I can only fear death. ~Carl Jung, The Red Book, Page 356.

I saw how we live toward death, how the swaying golden wheat sinks together under the scythe of the reaper, / like a smooth wave on the sea-beach. ~Carl Jung, The Red Book, Page 268.

You may call me death-death that rose with the sun. I come with quiet pain and long peace. I lay the cover of protection on you. In the midst of life begins death. I lay cover upon cover upon you so that your warmth will never cease. ~A Dark Form to Philemon, Liber Novus, Page 355.

In this bloody battle death steps up to you, just like today where mass killing and dying: fill the world. The coldness of death penetrates you. When I froze to death in my solitude, I saw dearly and saw what was to come, as clearly as I could see the stars and the distant mountains on a frosty night. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 274, Footnote 73.

Since what takes place in the secret hour of life's midday is the reversal of the parabola, the birth of death …Not wanting to live is identical with not wanting to die. Becoming and passing away is the same curve. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 274, Footnote 75.

After death on the cross Christ went into the underworld and became Hell. So he took on the form of the Antichrist, the dragon. The image of the Antichrist, which has come down to us from the ancients, announces the new God, whose coming the ancients had foreseen. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 242.

Therefore after his death Christ had to journey to Hell, otherwise the ascent to Heaven would have become impossible for him. Christ first had to become his Antichrist, his under worldly brother. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 244.

I saw a terrible flood that covered all the northern and low-lying lands between the North Sea and the Alps. It reached from England up to Russia, and from the coast of the North Sea right up to the Alps. I saw yellow waves, swimming rubble, and the death of countless thousands. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 231.

Look back at the collapse of empires, of growth and death, of the desert and monasteries, they are the images of what is to come. Everything has been foretold. But who knows how to interpret it? ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 236.

But above all protect me from the serpent of judgment, which only appears to be a healing serpent, yet in your depths is infernal poison and agonizing death. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 238.

The spirit of the depths is pregnant with ice, fire, and death. You are right to fear the spirit of the depths, as he is full of horror. You see in these days what the spirit of the depths bore. You did not believe it, but you would have known it if you had taken counsel with your fear. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 238.

The black beetle is the death that is necessary for renewal; and so thereafter, a new sun glowed, the sun of the depths, full of riddles, a sun of the night. And as the rising sun of spring quickens the dead earth, so the sun of the depths quickened the dead, and thus began the terrible struggle between light and darkness. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 238.

I went through a torment unto death and I felt certain that I must kill myself if I could not solve the riddle of the murder of the hero. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 242.

The three days descent into Hell during death describes the sinking of the vanished value into the unconscious, where, by conquering the power of darkness, it establishes a new order, and then rises up to heaven again, that is, attains supreme clarity of consciousness. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Footnote 135, Page 243.

That is the ambiguity of the God: he is born from a dark ambiguity and rises to a bright ambiguity. Unequivocalness is simplicity and leads to death. But ambiguity is the way of life. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 244.

I saw it, I know that this is the way: I saw the death of Christ and I saw his lament; I felt the agony of his dying, of the great dying. I saw a new God, a child, who subdued daimons in his hand. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 254.

You're stubborn. What I mean is that it's hardly a coincidence that the whole world has become Christian. I also believe that it was the task of Western man to carry Christ in his heart and to grow with his suffering, death, and resurrection. ~Carl Jung to The Red One, Liber Novus, Page 260.

Death is the hardest thing from the outside and as long as we are outside of it. But once inside you taste of such completeness and peace and fulfillment that you don't want to return. ~Carl Jung, Letters Volume 1, Pages 355-357.

It frequently happens that when a person with whom one was intimate dies, either one is oneself drawn into the death, so to speak, or else this burden has the opposite effect of a task that has to be fulfilled in real life. ~Carl Jung, Letters Volume 1, Page 239.

Psychology is a preparation for death. We have an urge to leave life at a higher level than the one at which we entered. ~Carl Jung; Conversations with C.G. Jung, Psychotherapy, Page 16.

Even though spirit is regarded as essentially alive and enlivening, one cannot really feel nature as unspiritual and dead. We must therefore be dealing here with the (Christian) postulate of a spirit whose life is so vastly superior to the life of nature that in comparison with it the latter is no better than death. ~Carl Jung; CW 9i; Para 390.

To put it in modern language, spirit is the dynamic principle, forming for that very reason the classical antithesis of matter-the antithesis, that is, of its stasis and inertia. Basically it is the contrast between life and death. The subsequent differentiation of this contrast leads to the actually very remarkable opposition of spirit and nature. ~Carl Jung; CW 9i; Para 390.

While the man who despairs marches towards nothingness, the one who has placed his faith in the archetype follows the tracks of life and lives right into his death. Both, to be sure, remain in uncertainty, but the one lives against his instincts, the other with them. ~Carl Jung; Memories Dreams and Reflections; Page 306.

The earthly fate of the Church as the body of Christ is modelled on the earthly fate of Christ himself. That is to say the Church, in the course of her history, moves towards a death. ~Carl Jung, Mysterium Coniunctionis, CW 14, par. 28, note 194.

Moreover, the unconscious has a different relation to death than we ourselves have. For example, it is very surprising in which way dreams anticipate death. ~Carl Jung, Children’s Dreams Seminar, Page 343.

The division into four is a principium individuationis; it means to become one or a whole in the face of the many figures that carry the danger of destruction in them. It is what overcomes death and can bring about rebirth. ~Carl Jung, Children’s Dreams Seminar, Page 372.

Only for outsiders, who have never been inside, is penal servitude not a hellish cruelty. I know many cases from my psychiatric experience where death would have been a mercy in comparison with life in a prison. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. 1, Pages 446-448.

Oh outstanding vessel of devotion and obedience! To the ancestral spirits of my most beloved and faithful wife Emma Maria. She completed her life and after her death she was lamented. She went over to the secret of eternity in the year 1955. Her age was 73. Her husband C.G. .Jung has made and placed [this stone] in 1956.

A point exists at about the thirty-fifth year when things begin to change; it is the first moment of the shadow side of life, of the going down to death. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Page 223.

The ego is an illusion which ends with death but the karma remains, it is given another ego in the next existence. ~Carl Jung, Modern Psychology, Vol. 3, Page 17.

A child, too, enters into this sublimity, and there detaches himself from this world and his manifold individuations more quickly than the aged. So easily does he become what you also are that he apparently vanishes. Sooner or later all the dead become what we also are. But in this reality we know little or nothing about that mode of being, and what shall we still know of this earth after death? ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. 1, Page 343.

… it would seem to be more in accord with the collective psyche of humanity to regard death as the fulfillment of life’s meaning and as its goal in the truest sense, instead of a mere meaningless cessation. Anyone who cherishes a rationalistic opinion on this score has isolated himself psychologically and stands opposed to his own basic nature. ~Carl Jung, CWs, 8, ¶807.

Death is psychologically as important as birth, and like it, is an integral part of life. ... As a doctor, I make every effort to strengthen the belief in immortality, especially with older patients when such questions come threateningly close. For, seen in correct psychological perspective, death is not an end but a goal, and life’s inclination towards death begins as soon as the meridian is passed. ~Carl Jung, CW 13, Para. 68.

The analysis of older people provides a wealth of dream symbols that psychically prepare the dreams for impending death. It is in fact true, as Jung has emphasized, that the unconscious psyche pays very little attention to the abrupt end of bodily life and behaves as if the psychic life of the individual, that is, the individuation process, will simply continue. … The unconscious “believes” quite obviously in a life after death. ~Marie-Louise von Franz (1987), ix.

Life's cessation, that is, death, can only be accepted as a reasonable goal either when existence is so wretched that we are only too glad for it to end, or when we are convinced that the sun strives to its setting "to illuminate distant races" with the same logical consistency it showed in rising to the zenith. ~Carl Jung, CW 8, Pages 399-403.

As a doctor I am convinced that it is hygienic—if I may use the word—to discover in death a goal towards which one can strive, and that shrinking away from it is something unhealthy and abnormal which robs the second half of life of its purpose. ~Carl Jung, CW 8, Pages 399-403.

Such a thing is possible only when there is a detachment of the soul from the body. When that takes place and the patient lives on, one can almost with certainty expect a certain deterioration of the character inasmuch as the superior and most essential part of the soul has already left. Such an experience denotes a partial death. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. 1, Pages 435-437.

Thus hun [Animus] means 'cloud-demon,' a higher 'breath-soul' belonging to the yang principle and therefore masculine. After death, hun rises upward and becomes shen, the 'expanding and self-revealing' spirit or god. ~Carl Jung, Secret of the Golden Flower, Page 114.

'Anima', called p'o, and written with the characters for 'white' and for 'demon', that is, 'white ghost', belongs to the lower, earth-bound, bodily soul, the yin principle, and is therefore feminine. After death, it sinks downward and becomes kuei (demon), often explained as the 'one who returns' (i.e. to earth), a revenant, a ghost. ~Carl Jung, Secret of the Golden Flower, Page 114.

The fact that the animus and the anima part after death and go their ways independently shows that, for the Chinese consciousness, they are distinguishable psychic factors which have markedly different effects, and, despite the fact that originally they are united in 'the one effective, true human nature', in the 'house of the Creative,' they are two. ~Carl Jung, Secret of the Golden Flower, Page 114.

Hun [Animus], then, would be the discriminating light of consciousness and of reason in man, originally coming from the logos spermatikos of hsing, and returning after death through shen to the Tao. ~Carl Jung, Secret of the Golden Flower, Page 116.

The creation and birth of this superior personality is what is meant by our text when it speaks of the 'holy fruit', the 'diamond body', or refers in other ways to an indestructible body. ~Carl Jung, The Secret of the Golden Flower, Page 123.

To the psyche death is just as important as birth and, like it, is an integral part of life. ~Carl Jung, The Secret of the Golden Flower, Page 124.

If viewed correctly in the psychological sense, death is not an end but a goal, and therefore life towards death begins as soon as the meridian is passed. ~Carl Jung, The Secret of the Golden Flower, Page 124.

The Chinese philosophy of yoga is based upon the fact of this instinctive preparation for death as a goal, and, following the analogy with the goal of the first half of life, namely, begetting and reproduction, the means towards perpetuation of physical life, it takes as the purpose of spiritual existence the symbolic begetting and bringing to birth of a psychic spirit body ('subtle body'), which ensures the continuity of the detached consciousness. ~Carl Jung, The Secret of the Golden Flower, Page 124.

The ego withdraws from its entanglement in the world, and after death remains alive because "interiorization" has prevented the wasting of the life-forces in the outer world. Instead of these being dissipated, they have made within the inner rotation of monad a centre of life which is independent of bodily existence. Such an ego is a god, deus, shen. ~Secret of the Golden Flower, Page 17.

He [Nietzsche] expressed it as “God is dead” and he did not realise that in saying this he was still standing within the dogma, for Christ's death is one of the secret mysteries of Christianity. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lectures, Page 197.

While we are in avidya, we act like automatons, we have no idea what we are doing. Buddha regarded this as absolutely unethical. Avidya acts in the sense of the concupiscentia and involves us in suffering, illness and death. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lecture XI, 3Feb1939, Page 74.

After my wife's death. . . I felt an inner obligation to become what I myself am. To put it in the language of the Bollingen house, I suddenly realized that the small central section which crouched so low, so hidden was myself! ~Carl Jung, MDR, Page 225.

Now I know the truth but there is a small piece not filled in and when I know that I shall be dead. ~Carl Jung [2 days before his death] ~Miguel Serrano, Two Friendships, Page 104.

The past decade dealt me heavy blows – the death of dear friends and the even more painful loss of my wife, the end of my scientific activity and the burdens of old age, but also all sorts of honors and above all your friendship, which I value the more highly because it appears that men cannot stand me in the long run. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Page 516.

Death is a drawing together of two worlds, not an end. We are the bridge. ~Carl Jung, J.E.T., Page 95.

Often people come for analysis who wish to be prepared to meet death. They can make astonishingly good progress in a short time and then die peacefully. ~Carl Jung, Jung-Ostrowski, Page16.

Christ’s redemptive death on the cross was understood as a “baptism,” that is to say, as rebirth through the second mother, symbolized by the tree of death… The dual-mother motif suggests the idea of a dual birth. One of the mothers is the real, human mother, the other is the symbolical mother. ~Carl Jung, CW 5, para 494-495.

Although there is no way to marshal valid proof of continuance of the soul after death, there are nevertheless experiences which make us thoughtful. I take them as hints, and do not presume to ascribe to them the significance of insights. ~Carl Jung, MDR, Page 312.

I was particularly interested in the dream which, in mid-August 1955, anticipated the death of my wife. It probably expresses the idea of life's perfection: the epitome of all fruits, rounded into a bullet, struck her like karma. C.G. Jung ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Page 310.

In the initiation of the living, however, this "Beyond" is not a world beyond death, but a reversal of the mind's intentions and outlook, a psychological "Beyond" or, in Christian terms, a "redemption" from the trammels of the world and of sin. ~Carl Jung, CW 11, Paragraph 813.

I can answer your question about life after death just as well by letter as by word of mouth. Actually this question exceeds the capacity of the human mind, which cannot assert anything beyond itself. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Page 561.

The imminence of death and the vision of the world in conspectu mortis is in truth a curious experience: the sense of the present stretches out beyond today, looking back into centuries gone by, and forward into futures yet unborn. ~Carl Jung, Letters, Vol. II, Page 10.

I'm inclined to believe that something of the human soul remains after death, since already in this conscious life we have evidence that the psyche exists in a relative space and in a relative time, that is in a relatively non-extended and eternal state. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 29-30.

There is no loneliness, but all-ness or infinitely increasing completeness. Such dreams occur at the gateway of death. They interpret the mystery of death. They don't predict it but they show you the right way to approach the end. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 145-146

What I mean by this is that every epoch of our biological life has a numinous character: birth, puberty, marriage, illness, death, etc. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 208-210.

It was the tragedy of my youth to see my father cracking up before my eyes on the problem of his faith and dying an early death. This was the objective outer event that opened my eyes to the importance of religion. Subjective inner experiences prevented me from drawing negative conclusions about religion from my father's fate, much as I was tempted to do so. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 257-264.

With no human consciousness to reflect themselves in, good and evil simply happen, or rather, there is no good and evil, but only a sequence of neutral events, or what the Buddhists call the Nidhanachain, the uninterrupted causal concatenation leading to suffering, old age, sickness, and death. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 310-311.

We ought to remember that the Fathers of the Church have insisted upon the fact that God has given Himself to man's death on the Cross so that we may become gods. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 312-316.

Mama's death has left a gap for me that cannot be filled. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 316-317.

Yahweh gives life and death. Christ gives life, even eternal life and no death. He is a definite improvement on Yahweh. He owes this to the fact that He is suffering man as well as God. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 471-473

When one has looked and laboured for a long time, one knows oneself and has grown old. - The "secret of life" is my life, which is enacted round about me, my life and my death; for when the vine has grown old it is torn up by the roots. All the tendrils that would not bear grapes are pruned away. Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 514-515

The "secret of life" is my life, which is enacted round about me, my life and my death; for when the vine has grown old it is torn up by the roots . All the tendrils that would not bear grapes are pruned away. Its life is remorselessly cut down to its essence, and the sweetness of the grape is turned into wine, dry and heady, a son of the earth who serves his blood to the multitude and causes the drunkenness which unites the divided and brings back the memory of possessing all and of the kingship, a time of loosening, and a time of peace. There is much more to follow, but it can no longer be told. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 514-515

It looks as if only those who are relatively close to death are serious or mature enough to grasp some of the essentials in our psychology, as a man who wants to get over an obstacle grasps a handy ladder. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 536-537

I try to accept life and death. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 546-547

Where I find myself unwilling to accept the one or the other [Life or Death] I should question myself as to my personal motives. . . . ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 546-547

Is it the divine will? Or is it the wish of the human heart which shrinks from the Void of death? ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 546-547

In ultimate situations of life and death complete understanding and insight are of paramount importance, as it is indispensable for our decision to go or to stay and let go or to let stay. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 546-547

As I have so earnestly shared in his [Victor White] life and inner development, his death has become another tragic experience for me. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Page 563

We still consider his [Socrates] daimonion as an individual peculiarity if not worse. Such people, says Buddha, "after their death reach the wrong way, the bad track, down to the depth, into an infernal world." ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Pages 531-533

We have to learn with effort the negations of our positions, and to grasp the fact that life is a process that takes place between two poles, being only complete when surrounded by death. ~Carl Jung, 1925 Seminar, Page 86

If we became aware of the ancestral lives in us, we might disintegrate. An ancestor might take possession of us and ride us to death. ~Carl Jung, 1925 Seminar, Page 139

How great the importance of psychic hygiene, how great the danger of psychic sickness, is evident from the fact that just as all sickness is a watered-down death, neurosis is nothing less than a watered-down suicide, which left to run its malignant course all too often leads to a lethal end. ~Carl Jung, C.G. Jung Speaking: Interviews and Encounters, Pages 38-46

Death is more enduring of all things, that which can never be cancelled out. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 323

Death gives me durability and solidity. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 323.

But many people are never quite born; they live in the flesh but a part of them is still in what Lamaistic philosophy would call the Bardo, in the life between death and birth, and that prenatal state is filled with extraordinary visions. ~Carl Jung, Visions Seminar, Page 424.

If the old were not ripe for death, nothing new would appear; and if the old were not injuriously blocking the way for the new; it could not and need not be rooted out. ~Carl Jung, CW 6, Para 446.

Death is a drawing together of two worlds, not an end. We are the bridge. ~Carl Jung, J.E.T., Page 95.

One needs death to be able to harvest the fruit. ~Carl Jung, Liber Novus, Page 275.

I have frequently been able to trace back for over a year, in a dream-series, the indications of approaching death, even in cases where such thoughts were not prompted by the outward situation. ~Carl Jung, CW 8, Para 809

Death, therefore, has its onset long before death. ~Carl Jung, CW 8, Para 809

We are so convinced that death is simply the end of a process that it does not ordinarily occur to us to conceive of death as a goal and a fulfilment, as we do without hesitation the aims and purposes of youthful life in its ascendance. ~Carl Jung, CW 8, Para 797

For when the soul vanished at death, it was not lost; in that other world it formed the living counterpale to the state of death in this world. ~Carl Jung, CW 16, Para 493

We can therefore understand why the nuptiae chymicae, the royal marriage, occupies such an important place in alchemy as a symbol of the supreme and ultimate union, since it represents the magic-by-analogy which is supposed to bring the work to its final consummation and bind the opposites by love, for “love is stronger than death.” ~Carl Jung, CW 16, Para 398

But when we penetrate the depths of the soul and when we try to understand its mysterious life, we shall discern that death is not a meaningless end, the mere vanishing into nothingness—it is an accomplishment, a ripe fruit on the tree of life. Nor is death an abrupt extinction, but a goal that has been unconsciously lived and worked for during half a lifetime. ~Carl Jung, CW 18, Para 1705-7