Introduction: Stephen Black interviewed Jung in July 1955, in order to record material for broadcast in connection with Jung’s Both birthday, 26 July.

Besides a radio interview (no. 3, below), Black conducted an interview for the BBC television feature "Panorama," of which a segment of about six minutes (no. 2, below) was broadcast.

The conversation took place on the terrace of Jung’s house at Kusnacht; the sounds of a motorboat on the lake and music at the beach resort next door are sometimes audible.

Emma Jung sat beside her husband—one sees her in the film—but did not take part in the interview. Subsequently, Stephen Black left broadcasting, became a physician, and emigrated to New Zealand.

Stephen Black: Professor Jung, could you tell me how it came about that psychological medicine came to be divided so sharply in the first half of this century into Freudian and Adlerian and Jungian philosophies?

Dr. Jung: Well, that is so.

Always in the beginning of a new science, or when a new problem is tackled in science, there are necessarily many different aspects, particularly in a science like psychology, and particularly so when an absolutely new factor has been brought into the discussion.

Stephen Black: Which was that?

Dr. Jung: In this case, it was the unconscious—the concept of the unconscious.

It has been a philosophical concept before—in the philosophy of Carl Gustav Carus and then his follower Eduard von Hartmann.

But it was a mere speculative concept.

The unconscious was a kind of philosophical concept at first, but through the discoveries by Freud it became a practical medical concept, because he discovered these mechanisms

or connections. . . . He made of it a medical science. This is empirical.

An empirical medical science.

That was an entirely new proposition.

And naturally quite a number of opinions are possible in the beginning, where one is insufficiently acquainted with the phenomena.

It needed many experiments and experiences until one could establish a general terminology, for instance, or even a doctrine.

Now, I never got as far as to produce a general doctrine, because I always felt we don’t know enough.

But Freud started the theory very early and so did Adler, because that can be explained by the human need for certainty.

You feel completely lost in such an enormous field as psychology represents.

And there you must have something to cling to, some guidance as it were, and that is probably the reason why this kind of psychology set out with almost ready-made theories.

At least, the theories were conceived in a moment when one didn’t know enough about the role of the psychology of the unconscious.

That is my private view, and so I’ve refrained from forming theories. Stephen Black: When you first met Freud—when was that, 1906?

Dr. Jung: That was 1907.

Stephen Black: Will you describe that meeting to me?

Dr. Jung: Oh, well, I just made a visit to him in Vienna and then we talked for thirteen hours without interruption.

Dr. Black: Thirteen hours without interruption? Dr. Jung: Thirteen hours without interruption!

We didn’t realize that we were almost dead at the end of it, but it was tremendously interesting. Stephen Black: Did you argue?

Carl Jung: Yes, I did, to a certain extent.

Of course, seeing him for the first time I had to get my bearings first. I had naturally also to listen to what he had to say.

And I was then a very young man still, and he was the old man and had great experience and he was of course way ahead of me and so I settled down to learn something first.

Stephen Black: And then in 1912 you published "The Psychology of the Unconscious."

Dr. Jung: Well, by 1912 I had acquired a lot of my own experience and I had learned a great deal from Freud and then I saw certain things in a different light.

Stephen Black: So you dissociated yourself from Freud.

Dr. Jung: Yes, because I couldn’t share his opinions of his convictions anymore with reference to certain things.

I mean in certain points I have no argument against him, but in other respects I disagree with him.

Stephen Black: What was it you disagreed most over at that time?

Dr. Jung: Well, that was chiefly the interpretation of psychological facts.

You know, he was on the standpoint of scientific materialism, which I consider as a prejudice, a sort of meta- physical presupposition, which I exclude.

Stephen Black: What in your view will be the final outcome of this kind of scientific quarrel between the vari- ous schools of medical psychology?

Dr. Jung: For the time being it is certainly a sort of quarrel, but in the course of time it will be as it always has been in the history of science.

You will see that certain points will be taken from Freud’s ideas, others from Adler’s ideas, and something of

my ideas.

There is no question of victory of one idea, of one way of looking at things.

Such victories are only obtained where it is a matter of pretension, of convictions, for instance, philosophical or religious convictions.

In science there is nothing of the kind, there is merely the truth as one can see it.

Stephen Black: Thank you. Professor Jung, there’s a body of opinion in the world today that all is not well with the technique of psychoanalysis, that it takes too long, it uses up too many medical man-hours, it costs too much money.

Have you felt that about your technique of analytical psychology?

Dr. Jung: That is perfectly true. It takes time, it costs money, it takes the right people and there are too few. But that is foreseen.

That is in the nature of the thing.

Man’s soul is a complicated thing and it takes sometimes half a lifetime to get somewhere in one’s psychological development.

You know it is by no means always a matter of psychotherapy or treatment of neuroses. Psychology has also the aspect of a pedagogical method in the widest sense of the word. It is something-A system of education.

It is an education. It is something like antique philosophy. And not what we understand by a technique.

It is something that touches upon the whole of man and which challenges also the whole of man—in the patient or whatever the receiving party is as well as in the doctor.

Stephen Black: But it’s a therapeutic process also.

Dr. Jung: Yes, you know, this procedure has many stages or levels.

If you take an ordinary case of neurosis, it may only go as far as healing the symptoms or giving the patient such an attitude that he can deal with his neurosis.

Sometimes it takes him a week, sometimes a few days, sometimes it is just one consultation in which I clean up a case. It is of course a question of knowing where, or what—it needs a good deal of experience.

But other cases take very long, and you couldn’t send them away because they wouldn’t go.

They want to know more, to make the whole process of development, which goes from stage to stage, a widening out of the mental horizon.

You cannot imagine how one-sided people are nowadays.

And so it needs no end of work to get people rounded out, or mentally more developed, more conscious. And they are so keen on it that for nothing in the world would they quit.

And they are not shy of spending money on it.

Stephen Black: Professor Jung, how does this compare with religion, with religious practice? Dr. Jung: I rather would prefer to say, how does it compare with antique philosophy.

You see, our religions are known as confessions. One confesses a certain creed. Now, of course, this has nothing to do with a creed.

It has only to do with the natural individuation process, namely, the process that sets in with birth, as it were.

As each plant, each tree grows from a seed and becomes in the end, say, an oak tree, so man becomes what he is meant to be.

At least, he ought to get there.

But most get stuck by unfavorable external conditions, by all sorts of hindrances or pathological distortions, wrong education—no end of reasons why one shouldn’t get there where one belongs.

Stephen Black: Do more people get stuck today than fifty years ago when you started? Dr. Jung: There are no statistics, and I wouldn’t have an opinion about it.

But I only know that there is an uncanny amount of people that get stuck unnecessarily.

They could get much further if they had heard the proper things or if they had spent the necessary time on themselves.

But this is not popular, you know, to spend time on oneself, because our point of view is entirely extraverted.

Stephen Black: One last question. You have defined these personality types of extravert and introvert.

Which are you?

Dr. Jung: Oh well. [Laughs.] Everybody would call me an introvert. Stephen Black: You’re an introvert. And what was Freud?

Dr. Jung: Now, that is a very difficult question.

You know, Freud is—and he doesn’t conceal it—he’s a neurotic type. And there it is very difficult to make out what the real type is.

For a long time you have to observe which mental contents are conscious and which are unconscious. And then only you can say this must be the original type.

I will say Freud’s point of view is an extraverted point of view. But as to his personal type I wouldn’t speculate.

Stephen Black: And Adler?

Dr. Jung: He is equally introverted.

Stephen Black: He extended your definition of the complex to the inferiority complex. What are your views on this all important inferiority complex?

Dr. Jung: Well, that is a thing that surely plays a very great role, almost just as great as the sex complex.

You see, the sex complex belongs to a hedonistic type of man who thinks in terms of his pleasure and displea- sure, while there is another class of man, chiefly the man who has not arrived, who thinks in terms of power and defeat, and to him it is far more important to win out somewhere than his whole sex problem.

Stephen Black: What should we think in terms of, in your view?

Dr. Jung: Obviously, life has the two aspects, namely, self-preservation and the preservation of species. There you have the two things.

Nobody in his senses dismisses the one or the other thing.

We always have both aspects, because we are meant to be balanced.

Introduction: During his visit to Kiisnacht, Stephen Black also conducted an interview for BBC radio.

According to the BBC transcript, it was recorded on July 29, 1955, and broadcast as part of a series, "Personal Call," on October

3. The text was printed as an appendix to E. A. Bennet’s book C. G. Jung (London, 1961), and Dr. Bennet dated it July

24. He had been given the

copyright in the transcript by the BBC and kindly permitted its publication here.

Stephen Black: "Vocatus atque non vocatus deus aderit" is a Latin translation of the Greek oracle, and, translated into English, it might read, "Invoked or not invoked the god will be present," and in many ways this expresses the philosophy of Carl Jung.

I am sitting now in a room in his house at Kusnacht, near Zurich, in Switzerland.

And as I came in through the front door, I read this Latin translation of the Greek, carved in stone over the door.

For this house was built by Professor Jung. How many years ago, Professor Jung?

Dr. Jung: Oh, almost fifty years ago.

Stephen Black: Why did you choose to put this over your front door?

Dr. Jung: Because I wanted to express the fact that I always feel unsafe, as if I’m in the presence of superior possibilities.

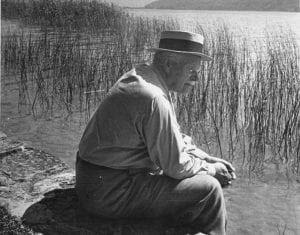

Stephen Black: Professor Jung is sitting opposite to me now.

He is a large man, a tall man, and this summer reached his eightieth birthday.

He has white hair, a very powerful face, with a small white mustache and deep brown eyes. He reminds me, with all respect, Professor Jung, of a typical peasant of Switzerland.

What do you feel about that, Professor Jung?

Dr. Jung: Well, I think you are not just beside the mark. That is what I often have been called.

Stephen Black: And yet Professor Jung is a man whose reputation far transcends the frontiers of this little country.

It’s a reputation which isn’t only European; it is world-wide and has made itself felt considerably in the Far East.

Professor Jung, how did you, as a doctor, become interested in psychological medicine?

Dr. Jung: Well, when I was a student of medicine I already then became interested in the psychological aspect—chiefly of mental diseases.

I studied, besides my medical work, also philosophy—chiefly Kant, Schopenhauer and others.

I found it very difficult in those days of scientific materialism to find a middle line between natural science or medicine and my philosophical interests.

And in the last of my medical studies, just before my final exam, I discovered the short introduction that Krafft-Ebing had written to his textbook of psychiatry, and suddenly I understood the connection between psychology or philosophy and medical science.

Stephen Black: This was due to Krafft-Ebing’s introduction to his textbook? Carl Jung: Yes; and it caused me tremendous emotion then.

I was quite overwhelmed by a sudden sort of intuitive understanding.

I wouldn’t have been able to formulate it clearly then, but I felt I had touched a focus.

And then on the spot I made up my mind to become a psychiatrist, because there was a chance to unite my philosophical interests with natural science and medical science; that was my chief interest from then on.

Stephen Black: Would you say that your sudden intuitive interest in something like that, your intuitive under- standing, had to some extent been explained by your work during all the years since?

Dr. Jung: Oh, yes; absolutely.

But, as you know, such an intuitive moment contains the whole thing in nucleo.

It is not clearly formulated; it’s an indescribable totality; but this moment had been the real origin of my career as a medical psychological scientist.

Stephen Black: So it was in fact Krafft-Ebing and not Freud that started you oft. Dr. Jung: Oh, yes, I became acquainted with Freud much later on.

Stephen Black: And when did you meet Freud? Dr. Jung: That was only in 1907.

I had some correspondence with him before that date, but I met him only in 1907 after I had written my book on The Psychology of Dementia Praecox.’

Stephen Black: That was your first book? Dr. Jung: That wasn’t really my first book.

The book on dementia praecox came after my doctor’s thesis in 1904.

And then my subsequent studies on the association experiment’ paved the way to Freud, because I saw that the behavior of the complex provided the experimental basis for Freud’s ideas on repression.

And that was the reason and the possibility of our relationship. Stephen Black: Would you like to describe to me that meeting?

Dr. Jung: Well, I went to Vienna and paid a visit to him, and our first meeting lasted thirteen hours. Stephen Black: Thirteen hours?

For thirteen uninterrupted hours we talked and talked and talked.

It was a tour d’horizon, in which I tried to make out Freud’s peculiar mentality.

He was a pretty strange phenomenon to me then, as he was to everybody in those days, and then I saw very clearly what his point of view was, and I also caught some glimpses already where I wouldn’t join in.

Stephen Black: In what way was Freud a peculiar personality? Dr. Jung: Well, that’s difficult to say, you know.

He was a very impressive man and obviously a genius.

Yet you must know the peculiar atmosphere of Vienna in those days: it was the last days of the old Empire, and Vienna was always spiritually and in every way a place of a very specific character.

And particularly the Jewish intelligentsia was an impressive and peculiar phenomenon—particularly to us Swiss, you know.

We were, of course, very different and it took me quite a while until I got it.

Stephen Black: Would you say, then, that the ideas and the philosophy which you have expressed have in their root something peculiarly Swiss?

Dr. Jung: Presumably.

You know, our political neutrality has much to do with it.

We were always surrounded by the great powers—those four powers, Germany, Austria, Italy, and France— and we had to defend our independence, so the Swiss is characterized by that peculiar spirit of independence, and he always reserves his judgment.

He doesn’t easily imitate, and so he doesn’t take things for granted. Stephen Black: You are a man, Professor Jung, who reserves his judgment? Dr. Jung: Always.

Stephen Black: In 1912 you wrote a book called Psychology of the Unconscious,’ and it was at that time that you, as it were, dissociated yourself from Freud?

Dr. Jung: Well, that came about quite automatically because I developed certain ideas in that book which I knew Freud couldn’t approve.

Knowing his scientific materialism I knew that this was the sort of philosophy I couldn’t subscribe to. Stephen Black: Yours was the introvert, to use your own terminology?

Dr. Jung: No. Mine was merely the empirical point of view.

I didn’t pretend to know anything, I wanted just to make the experience of the world to see what things are. Stephen Black: Would you accuse Freud of having become involved in the mysticism of terms?

Dr. Jung: No; I wouldn’t accuse him; it was just a style of the time.

Thought, in a way, about psychological things was just, as it seems to me, impossible—too simple. In those days one talked of psychiatric illness as a sort of by-product of the brain.

Joking with my pupils, I told them of an old textbook for the Medical Corps in the Swiss Army which gave a description of the brain, saying it looked like a dish of macaroni, and the steam from the macaroni was the psyche.

That is the old view, and it is far too simple.

So I said: "Psychology is the science of psychic phenomena."

We can observe whether these phenomena are produced by the brain, or whether they are there in their own right—they are just what they are.

I have no theory about the origin of the psyche.

I take phenomena as they are and I try to describe them and to classify them, and my terminology is an em- pirical terminology, like the terminology in botany or zoology.

Stephen Black: You’ve travelled a great deal? Dr. Jung: Yes; a lot.

I have been with Navaho Indians in North America, and in North Africa, in East and Central Africa, the Sudan and Egypt, and in India.

Stephen Black: Do you feel that the thought of the East is in any way more advanced than the thought in the West?

Dr. Jung: Well, you see, the thought of the East cannot be compared with the thought in the West; it is in- commensurable.

It is something else.

Stephen Black: In what way does it differ, then?

Dr. Jung: Well, they are far more influenced by the basic facts about psychology than we are. Stephen Black: That sounds more like your philosophy.

Dr. Jung: Oh, yes; quite.

That is my particular understanding of the East, and the East can appreciate my ideas better, because they are better prepared to see the truth of the psyche.

Some think there is nothing in the mind when the child is born, but I say everything is in the mind when the child is born, only it isn’t conscious yet.

It is there as a potentiality.

Now, the East is chiefly based upon that potentiality.

Stephen Black: Does this contribute to the happiness of people one way or the other? Are people happier in themselves in the East?

Dr. Jung: I don’t think that they are happier than we are.

You see, they have no end of problems, of diseases and conflicts; that is the human lot.

Stephen Black: Is their unhappiness based upon their psychological difficulties, like ours, or it is more based upon their physical environment, their economics?

Dr. Jung: Well, you see, there is no difference between, say, unfavorable social conditions and unfavorable psychological conditions.

We may be, in the West, in very favorable social conditions, and we are as miserable as possible—inside. We have the trouble from the inside.

They have it perhaps more from the outside.

Stephen Black: And have you any views on the reason for this misery we suffer here? Dr. Jung: Oh, yes; there are plenty of reasons.

Wrong values—we believe in things which are not really worthwhile.

For instance, when a man has only one automobile and his neighbor has two, then that is a very sad fact and he is apt to get neurotic about it.

Stephen Black: In what other ways are our values at fault?

Well, all ambitions and all sorts of things—illusions, you know, of any description. It is impossible to name all those things.

Stephen Black: What is your view, Professor Jung, on the place of women in society in the Western world? Dr. Jung: In what way ? The question is a bit vague.

Stephen Black: You said just now, Professor Jung, that some of our difficulties arose out of wrong values, and I’m trying to find out whether you feel those wrong values arise in men as a result of the demands of women.

Dr. Jung: Sometimes, of course, they do, but very often it is the female in a man that is misleading him.

The anima in man, his feminine side, of which he is truly unaware, is causing his moods, his resentments, his prejudices.

Stephen Black: So that the woman who wants two cars because a neighbor has two cars, is only stimulating ...?

Dr. Jung: No, perhaps she simply voices what he has felt for a long time.

He wouldn’t dare to express it, but she voices it—she is, perhaps, naïve enough to say so. Stephen Black: And what does the man express of the woman’s animus?

Dr. Jung: Well, he is definitely against it, because the animus always gets his goat, it calls forth his anima affects and anima moods; they get on each other’s nerves.

Listen to a conversation between a man and wife when there is a certain amount of emotion about them.

You hear all the wonderful arguments of an anima in the man; he talks then like a woman, and she talks like a man, with very definite opinions and knows all about it.

Stephen Black: Do you feel that there’s any hope of adjusting this between a man and a woman, if they understand it in your terms?

Dr. Jung: Well, you see, that is one of the main reasons why I have developed a certain psychology of relationship—for instance, the relationship in marriage, and how a man and his wife should understand each other or how they misunderstand each other practically. That’s a whole chapter of psychology and not an unimportant one.

Stephen Black: Which is the basic behavior? The Eastern? Dr. Jung: Neither.

The East is just as one-sided in its way as the West is in its way.

I wouldn’t say that the position of the woman in the East is more natural or better than with us.

Civilizations have developed styles. For instance, a Frenchman or an Italian or an Englishman show very different and very characteristic ways in dealing with their respective

wives.

I suppose you have seen English marriages, and you know how an English gentleman would deal with his wife in the event of trouble, for instance; and if you compare this with an Italian, you will see all the difference in the world.

You know, Italy cultivates its emotions.

Italians like emotions and they dramatize their emotions. Not so the English.

Stephen Black: And in India or Malaya?

Dr. Jung: In India, presumably the same; I had no chance to assist in a domestic problem in India, happily

enough.

It was a holiday from Europe, where I had had almost too much to do with domestic problems of my patients—that sort of thing was my daily bread.

Dr. Jung: Would you say, then, as a scientific observation that there is, in fact, less domestic trouble in the East than in the West?

Dr. Jung: I couldn’t say that.

There is another kind of domestic problem, you know.

They live in crowds together in one house, twenty-five people in one little house, and the grandmother on top of the show, which is a terrific problem.

Happily enough, we have no such things over here.

Stephen Black: At the end of his life, Freud, one feels, had some dissatisfaction with the nature of psychoanalysis, the length of time involved in the treatment of mental illness and so on.

Have you, now you’re eighty years old, felt any dissatisfaction with your work? Dr. Jung: No; I couldn’t say so.

I know I’m not dissatisfied at all, but I have no illusions about the difficulty of human nature. You see, Freud was always a bit impatient; he always hoped to find some short-cut.

And I knew that is just the thing we would not find, because anything that is good is expensive. It takes time, it requires your patience and no end of it.

I can’t say I am dissatisfied.

And so I always thought anything, if it is something good, will take time, will demand all your patience, it will be expensive.

You can’t get around it.

Stephen Black: How did you meet your wife? Is she connected with your work?

Dr. Jung: Well, I met her when she was quite a young girl, about fifteen or sixteen, and I just happened to see her, and I said to a friend of mine—I was twenty-one then—I said, "That girl is my wife."

Stephen Black: Before you’d spoken to her?

Dr. Jung: Yes. "That’s my wife." I knew it. I saw her on top of a staircase, and I knew: "That is my wife." Stephen Black: How many children have you got?

Dr. Jung: Five children, nineteen grandchildren, and two greatgrandchildren.

Stephen Black: Has any of this large family followed in your footsteps?

Dr. Jung: Well, My son is an architect and an uncle of mine was an architect.

None has studied medicine—all my daughters married—but they are very interested and they "got it" at home, you see, through the atmosphere.

One nephew is a doctor.

Stephen Black: Were you interested in architecture at all?

Dr. Jung: Oh, yes; very much so. I have built with my own hands; I learned the work of a mason. I went to a quarry to learn how to split stones—big rocks.

Stephen Black: And actually laying bricks, laying the stones? Dr. Jung: Oh, well, in Europe we work with stone.

I did actually lay stones and built part of my house up in Bollingen. Stephen Black: Why did you do that?

Dr. Jung: I wanted to handle and get the feeling of the stone and to touch the earth—I worked a lot in the garden, I have chopped wood, felled trees, and all that. I liked sailing and rowing and mountain climbing when I was young.

Stephen Black: Could you explain what you think are the origins of this desire to touch the earth? We in England have it very much; every Englishman has his little garden.

We all love the earth.

Dr. Jung: Of course. Well, you know, that is—how can we explain it?—you love the earth and the earth loves you.

And therefore the earth brings forth.

That is so even with the peasant who wants to make his field fertile, and in the night of the full moon he sleeps with his wife in the furrow.

Stephen Black: Professor Jung, what do you think will be the effect upon the world of living, as we have been living, and may still have to live, under the threat of the hydrogen bomb?

Dr. Jung: Well, that’s a very great problem.

I think the West is more affected by it than the East, because the East has a very different attitude to death

and destruction.

Think, for instance, of the fact that practically the whole of India believes in reincarnation, so when you lose this life you have plenty of others.

It doesn’t matter so much.

Moreover, this world is illusion anyhow, and if you can get rid of it, it isn’t so bad. And if you hope for a further life, well, you have untold possibilities ahead of you.

Since in the West there is one life only, therefore I can imagine that the West is more disturbed by the possibility of utter destruction than the East.

We have only one life to lose and we are by no means assured of a number of other lives to follow.

The greater part of the European population doesn’t even believe in immortality anymore and so, once destroyed, forever destroyed.

That explains a great deal of the reaction in the West.

We are more vulnerable because of our lack of knowledge and contact with the deepest strata of the psyche.

But the East is better defended in that way, because it is based upon the fundamental facts of the human soul and believes more in it and in its possibilities than the West.

And that is a point of uncertainty in the West.

It is a very critical point. Carl Jung, C.G. Jung Speaking: Interviews and Encounters, Pages 252-267.