Introduction: The tenth International Medical Congress for Psychotherapy was held at Oxford from July 29 to August 2, 1938.

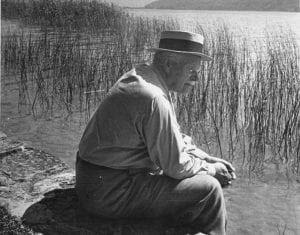

Jung presided, in his capacity as president of the International General Medical Society for Psychotherapy,’ which sponsored the Congress.

On August 1, at the request of a number of doctors at the Congress, Jung participated in a question-and-answer session, which was recorded in shorthand by Derek Kitchin.

The transcript has been in private hands and is published here for the first time.

Question 1. What is your view on the exact nature of psychic causation? Dr. Jung: That sounds very dangerous, but it is not so terrible.

It means really the question of causality versus finality.

It is a simple fact of logic that you can explain a sequence of events either from A to Z or from Z to A.

You may say that A is the big causa prima, the absolute causa efficiens from which depends the sequence as a sequence; or you can consider the Z as the final cause, which has an attractive effect upon the events which precede it.

This simply means that we take the sequence of events which we observe as a solid connection.

In itself it is not a solid connection at all.

The sequence of events has perhaps no connection whatever.

If we try to explain the sequence we have got to apply the idea that there is a connection.

We cannot help that: the idea of causation is a category of judgment a priori, and we cannot look at any se- quence of events without applying that category is not quite correct.

We might have said: “You cannot look at a sequence of events without applying the idea of connection." The idea of causality itself is a thoroughly magical idea.

We assume that this thing here, the causa prima, has a virtue, that of producing subsequent events.

So we make the same assumption about the final cause: that it has the virtue of attracting a series of events towards itself so that it appears to be the result, the goal, the aim.

That is mere assumption.

It is the way our mind deals with a sequence of events.

Now, as everywhere in natural science, and also in psychology and psychotherapy, we consider the sequence of psychic events as a connection, a solid sequence, that either begins with a prime cause or follows a final cause.

Both ways have been applied: the Freudian point of view is a strict causality point of view, and the Adlerian point of view is as strict a final-cause point of view.

I handle the case more skeptically.

I should say that if we have to apply the cause either way, we want to explain either way.

Any biological process has two aspects: you can explain it either from the beginning or from the end. You have "Either—or," or rather, "Either—and/or."

You have to say that it is surely in a way a causation, but the causa prima has a sort of magical effect.

At the same time, inasmuch as it is purposive, teleological, it is also directed by the final cause, or by the idea of the goal, or whatever you like to call it.

I take the whole question of causation as a problem of the theory of cognition.

Question 2. How would you define volition? What, in your view, is the relationship of the volitional process to the process of repression and inhibition?

Dr. Jung: That also is a very central problem.

It is of great interest to me that such questions should be asked at all.

I think it is very important.

I always hold that psychology is such a complicated chapter of human knowledge that those who deal with it should really have some philosophical preparation.

Medical psychology, surely, cannot stand alone.

This is a science much too big for our medical preparation. We medical people ought to take loans from other sciences.

For instance, we should have some knowledge of primitive psychology, of history, philosophy, and so on.

Many things with which we are grappling in our psychology could be simplified and made easier by knowledge that we have gained in other spheres.

Therefore we have a natural tendency to simplify and to create, at least for ourselves, a terminology which is generally understandable.

But I am thoroughly convinced that we shall not be able to evolve such a teminology from medical psychology alone.

That would always remain a sort of slang, a medical slang, and we have plenty of such slang already; I don’t advocate any further increase of that kind of thing.

I am also a strong adherent of the idea that our terminology should be correct.

We should not use hybrid words, or badly constructed Graeco-Latin terms; words of entirely wrong deriva- tion.

You know that the terminology in the field of medical psychology is still in the state of the old Babylonian con- fusion of tongues.

It really is so, as it is said in Green Pastures, that when the Lord heard those people cursing while they were building the tower of Babel he turned them all into foreigners and sent them all to Europe.

People speak different languages in Europe; they don’t do so in America.

This definition of volition: here I can only give you my own point of view, which is quite subjective.

It is a mere proposition, which I submit to further discussion.

I hold that this question ought to be settled with the help of primitive psychology.

Many of our difficulties would vanish if we had a better knowledge of primitive psychology. You know, perhaps, that I have done some work along that line.

I have been to primitive countries and I have done actual field work with primitives, in order to gain an imme- diate impression of the primitive mind.

I can assure you that what we call "will" or "volition" is a phenomenon that does not exist with primitives, or only in traces.

I will give you a very simple example.

Once I wanted to send a letter to a very distant station, about 120 kilometres from the place where we were.

The chief sent me a man, a runner, and I gave him my letter, and said, "Here is the letter, now you go down to the station."

The man simply stared at me as if he did not understand a word.

I spoke his language—that means, I spoke the pidgin Swahili; he understood it, but it did not reach him some- how.

I did not know what the matter was. I repeated, "Here is the letter, and now you go."

He went on staring at me as he had before, as if he did not understand a word, but he seemed willing.

I said, "That man is idiotic." In the meantime my headman, a Somali, came up and said, "You don’t do it in the right way."

He took a whip and began to dance up and down in front of that good native, and curse him up and down, and his ancestors and his children; and so that man began to wake up, wondering what great thing was in store for him: he heard that this here is the great white man who wants to send a letter to the other white man at the station, and that he should run in such and such a way; and then the messenger’s staff was brought, a cleftstick, and the letter was put into the cleavage, and that was handed to him, and then he was shown how he should run.

And during all that procedure that man’s face came up like the sun on Sunday morning; a large grin appeared, and he grasped it; then he went off, and in one stretch he ran that 120 kilometres.

That is a very simple example of how it ought to be done in many cases.

Every primitive needs the rite d’entree, which is what some people call the procedure about which I have told you.

This means that you must put his mind into the frame of doing, if you want something outside the ordinary.

Naturally, if it is something of his every-day, there is a certain adaptation, a certain attitude to it; but if he has to bring a letter somewhere, that is something else.

To us it is nothing extraordinary, but to him it is an extraordinary thing, and that thing needs a rite d’entree. Hunting is for many tribes not an ordinary affair, so they have a special rite d’entrie for hunting.

They work themselves up into the state of doing the special thing.

For instance, the Australian aborigines have a special routine for making a man angry, in order to get the idea into him that he should avenge a man who has been killed by another tribe.

It is done in a very elaborate way, the waking-up ceremonial.

I cannot go into details, but at the very moment when that man is thoroughly awake, you tell him that the man has been killed and that he ought to do something about it; and then the whole tribe wakes up and seeks the enemy.

If they find him, there will be a battle about it, but if they don’t find him, the excitement subsides, and every- one goes home as if nothing had happened.

This shows that the will was practically non-existent and that it needed all that ceremonial which you observe in primitive tribes to bring up something that is an equivalent of our word "decision."

Slowly through the ages we have acquired a certain amount of will power.

We could detach so much energy from the energy of nature, from the original unconsciousness, from the orig- inal flow of events, an amount of energy we could control.

We can say now, "I have made up my mind, I am going to do this and that,"with a certain amount of energy.

I cannot exceed that amount of energy; I have only a certain amount of will power.

So you say, when the task is too difficult or when there are too great inhibitions, "I cannot carry through my decision."

There are people who have a lot of will power at their disposal, and others who have very little.

Also, as you know, the education of children consists to a great extent of building up that volition, because it is not there to begin with.

We see them in extraordinary situations, these ancient rites d’entree.

All rites are in a way rites d’entree or rites de sortie, which are meant to get us out of a certain predicament.

One of the most striking examples of the rite de sortie is when a tribe has been making war on another tribe and a man has succeeded in killing somebody.

Then, of course, he is a great warrior; then he is all excited and he comes home. You would expect a wonderful reception.

Not at all; they catch him before he enters the village, the great, victorious hero, and they put him in a little but and they feed him on a vegetarian diet for a few months in order to get him out of his blood-thirst—which is a very recommendable thing!

Now, what we do, or what we decide, is not all willpower or volition, because we are acting a great deal on instinct, and instinct has no merit at all.

That is no moral decision; we are simply moved to do something, just as it happens. Instinctive reaction has the quality of "all or none."

It happens or it does not happen.

With the will it is an entirely different proposition.

The will, volition, is a moral action, and naturally it has a direct connection with repression and inhibition. You can repress instincts by your will, easily or, it may be, with great difficulty.

You cannot bring about so-called sublimation by means of instinct; that will not happen. But you can bring it about by volition.

Inhibition can be an absence of will; for instance, when you want to do something, you really wish it, but you cannot carry it out because your volition is inhibited; the energy is absent, it is taken away.

On the primitive level that phenomenon is a very frequent one; it is the loss of the soul; it has that quality.

There are many patients who will tell you that today they have no libido at all; or that suddenly, when they woke up in the morning, their libido had gone, or that at a certain moment during the day it had

vanished.

They have what the people in South America call "lost the gana."

It is a peculiar concept, and shows exactly what that is, I mean that loss. For instance, Argentine people play tennis; a ball jumps over the fence.

There is a little Indian girl outside, and the people inside ask her to throw the ball in. She sadly stares at the people and does nothing.

Then naturally they ask her, "Why don’t you throw the ball over the fence?" "I have no gana," no pleasure in doing it.

"I can’t do it, because I have no pleasure in it"; and then you can’t do it.

That, you see, is a primitive concept. Gana is what we would call libido, or energy, or volition. When gana is absent, that is an excellent motive.

For instance, when somebody asks you a favor, and you say, "I’m sorry, it doesn’t please me," or that you don’t like it, that is very impolite.

But in South America it is different. There people understand what it means when you say it doesn’t please you; that is enough.

You say, "I have no gana"; that counts.

There is also a social recognition of the extraordinarily important fact whether somebody is pleased to do something or not.

With us this apparently does not count at all. I am afraid that is a piece of primitive psychology. That is what we call an inhibition.

I should think it would be of a certain importance for our medical psychology if we could consider these primitive conditions a bit more.

Many things could then be explained in a way that would allow primitive psychology to come in without medi- cal knowledge.

Question 3. In what respect, if any, does the treatment of neurosis in the second half of life—that means af- ter thirty—differ from that in the first half of life?

Dr. Jung: This is also a question which you could discuss for several hours.

It is quite impossible for me to go into details; I only can give you a few hints.

The first half of life, which I reckon lasts for the first 35 or 36 years, is the time when the individual usually expands into the world.

It is just like an exploding celestial body, and the fragments travel out into space, covering ever greater distances.

So our mental horizon widens out, and our wishes and expectation, our ambition, our will to conquer the world and live, go on expanding, until you come to the middle of life.

A man who after forty years has not reached that position in life which he had dreamed of is easily the prey of disappointment.

Hence the extraordinary frequency of depressions after the fortieth year.

It is the decisive moment; and when you study the productivity of great artists—for instance, Nietzsche—you find that at the beginning of the second half of life their modes of creativeness often change.

For instance, Nietzsche began to write Zarathustra, which is his outstanding work, quite different from every- thing he did before and after, when he was between 37 and 38.

That is the critical time. In the second part of life you begin to question yourself.

Or rather, you don’t; you avoid such questions, but something in yourself asks them, and you do not like to hear that voice asking "What is the goal?"

And next, "Where are you going now?"

When you are young you think, when you get to a certain position, "This is the thing I want." The goal seems to be quite visible.

People think, "I am going to marry, and then I shall get into such and such a position, and then I shall make a lot of money, and then I don’t know what."

Suppose they have reached it; then comes another question: "And now what?

Are we really interested in going on like this forever, for ever doing the same thing, or are we looking for a goal as splendid or as fascinating as we had it before?"

Then the answer is: "Well, there is nothing ahead. What is there ahead?

Death is ahead."

That is disagreeable, you see; that is most disagreeable.

So it looks as if the second part of life has no goal whatever. Now you know the answer to that.

From time immemorial man has had the answer: "Well, death is a goal; we are looking forward, we are work- ing forward to a definite end."

The religions, you see, the great religions, are systems for preparing the second half of life for the end, the goal, of the second part of life.

Once, through the help of friends, I sent a questionnaire to people who did not know that I was the originator of the questionnaire.

I had been asked the question, "Why do people prefer to go to the doctor instead of to the priest for confession?"

Now I doubted whether it was really true that people prefer a doctor, and I wanted to know what the general public was going to say.

By chance that questionnaire came into the hands of a Chinaman, and his answer was, "When I am young I go to the doctor, and when I am old I go to the philosopher."

You see, that characterizes the difference: when you are young, you live expansively, you conquer the world; and when you grow old, you begin to reflect.

You naturally begin to think of what you have done.

There a moment comes, between 36 and 40—certain people take a bit longer—when perhaps, on an uninteresting Sunday morning, instead of going to church, you suddenly think, "Now what have I lived last year?" or something like that; and then it begins to dawn, and usually you catch your breath and don’t go on thinking because it is disagreeable.

Now, you see, there is a resistance against the widening out in the first part of life—that great sexual adventure.

When young people have resistance against risking their life, or against their social career, because it needs some concentration, some exertion, they are apt to get neurotic.

In the second part of life those people who funk the natural development of the mind—reflection, prepara- tion for the end—they get neurotic too.

Those are the neuroses of the second part of life.

When you speak of a repression of sexuality in the second part of life, you often have a repression of this, and these people are just as neurotic as those who resist life during the first part.

As a matter of fact it is the same people: first they don’t want to get into life, they are afraid to risk their life, to risk their health, perhaps, or their life for the sake of life, and in the second part of life they have no time.

So, you see, when I speak of the goal which marks the end of the second half of life, you get an idea of how far the treatment in the first half of life, and in the second halfi of life, must needs be different.

You get a problem to deal with which has not been talked of before. Therefore I strongly advocate schools for adult people.

You know, you were fabulously well prepared for life.

We have very decent schools, we have fine universities and that is all preparation for the expansion of life.

But where have you got the schools for adult people? for people who are 40, 45, about the second part of life?

Nothing.

That is taboo; you must not talk of it; it is not healthy.

And that is how they get into these nice climacteric neuroses and psychoses.

Question 4. Would you say that the attitude to be attained in the second half of life should be conceived as

one of the objective type rather than as one of sublimation? Dr. Jung: This is a profound and very ticklish question.

You see, in the first part of life it seems that sublimation is the thing indicated, and in the second part of life it seems that objectivity is indicated.

Now, what is sublimation?

This term has been taken from alchemy.

It is really an alchemical term, and when you understand it in that sense it does not evoke the psychological fact which we understand as sublimation.

Sublimation means that you don’t do what you really wish to do, and play the piano instead. That is nice, you see!

Or, instead of giving way to your terrible passions, you go to Sunday school. Then you say you have sublimated it—"it"!

It is, of course, an act of volition.

I don’t want to ridicule it at all, only sometimes it has a somewhat humorous aspect. Life, in spite of its misery, sometimes has an exceedingly humorous aspect.

And so those people who perform miracles of moral self-restraint occasionally look rather comical. It would be bad if this were not so; there would be no fun in life at all.

So even sublimation, which is a very useful and heroic thing, sometimes looks a bit funny; but it is never a se- rious thing, and it is certainly a way of dealing with the difficulties of life, all those difficulties that are forced upon us by our original nature.

We have a very unruly and passionate nature, perhaps, and we simply hurt ourselves if we live it in an uncon- trolled way.

Try to tell the truth.

We would like to tell the truth, I am sure. Nobody likes to lie if he is not forced to.

But just tell the truth for twenty-four hours and see what happens! In the end you can’t stand yourself any more.

So, you see, you can’t let go of all your ambitions; you can’t beat down every man who gets your goat; you can’t express your admiration to every pretty woman you see.

You must control yourself, after all, and that is also a considerable piece of sublimation.

Take swearing: you must not use this impossible language, and so, instead of saying something disagreeable, you say something agreeable, as you have learnt, and all that continues—ethics, self-repression, and sublimation.

And the worse your passions are, the more you must use this sublimation mechanism, otherwise you get into hot water.

And you don’t like that either.

Now surely the passions are likely to be worse in the first half of life than in the second.

There is a certain saying about the virtues of Solomon and David, who grew virtuous on account of their old age.

There is also a French saying: "Si jeunesse savait, si vieillesse pouvait!"

En fin, in the second half of life people have a chance to be more virtuous, somehow.

They don’t make enough use of that chance, and that comes from the fact that, unfortunately, they have learned more objectivity than sublimation.

They say, for instance, "Oh well, after all, it seems to be human nature that one has certain weaknesses"; so they begin to allow themselves certain weaknesses, and gradually, the more the passions

subside, the more you can yourself allow to side-step a little bit, to make little mistakes and to excuse yourself by saying it is not so terribly serious after all.

An elderly gentleman, of course, can allow himself to show some tenderness to a nice young girl.

Formerly he would have blushed; it would have been shocking; but now he can show his appreciation and everyone will say, "How nice and fatherly that is

Also, ladies of a certain age can allow themselves to have very liberal views, and to express such views, and among those are things which they never would have said before in younger age, because it would have been too shocking.

But when they are older one thinks, "That’s nice; that shows a certain experience of life"; and they are very free in the way in which they express themselves.

That is great objectivity; that is already the beginning of a certain philosophy that deals with facts as they are. It is perhaps a sort of disillusionment, or perhaps it is a sort of superiority gained through experience of life.

You know that your virtues are not going to increase very considerably any more. Even your virtues grow gray hair and become bald.

And so, what can you do?

You say, "Oh, that’s fine; you mustn’t expect too much."

And that is how we deal with ourselves in the second part of life.

I do not speak of how the analyst ought to deal with his patients.

There is an "ought," but there is a certain wisdom, and that belongs to the secrets of the art, which I shall not reveal here!

Question 5. Would you give us some hints with regard to religious experience? Is a so-called religious feeling a valid psychological experience?

Dr. Jung: Well, I understand this question in the following way. Is the religious experience a valid experience?

What is a valid experience?

For instance, if a dog bites me, is that a valid experience?

It is an experience; and if I have a religious experience, well, that is an experience too, and how shall I say that it is valid?

You might say, "Oh, you have an imagination, you have an illusion; you think that you had a religious experi- ence."

Well, that does not concern me. Perhaps it is an illusion; how do I know? There is no criterion.

I can only say, "I felt it like this."

Of course, you can draw conclusions, and so you can ask, "Are the conclusions you draw from it valid?"

For instance, you can draw the conclusion that you have an experience of your patron saint, who has appeared to you, or you have seen the Mother of God, or something like that.

Then you can ask, "Is that valid? Is that interpretation valid?" You know how divided opinions are.

Opinions are geographically rather different.

For instance, a vision with us will be interpreted in terms of traditional Christianity; several hundred miles more South, in terms of Islamic mentality, and a little bit more East, it will be something else again; and sometimes there is a considerable difference in the interpretation of such experiences, but the experiences themselves are always valid—because they exist.

For instance, is it a valid fact that there are elephants?

You cannot even say that elephants are needed; you only can say they exist.

And so with such experiences.

The moment a man says, "I had a religious experience," you can only say, "Well, you had a religious experi- ence."

You can hold all sorts of views about it.

You can say, "Oh, that was merely because your stomach was not all right, or you have slept badly." But that is merely explaining away the fact that he had such an experience.

Of course you can say, "Well, that may be quite pathological."

And in that case you must go to the Encyclopaedia Britannica and look up that kind of experience. All human experiences, you know, are registered in the Encyclopaedia Britannica!

And then you will be taught whether there was that experience, and of what kind.

But it may be that it is not contained in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, and in that case you can say, "Well, I have never heard of such an experience; I don’t know what it is," and you have got to explain it to yourself somehow.

But, generally speaking, religious experience is something we are fairly well acquainted with.

We have the history of religions; we have innumerable texts which inform us about the forms of religious ex- perience.

So we know it is a universal phenomenon, and if it is absent, then we are confronted with an abnormal case.

If somebody should say, "I don’t know what a religious experience is," then I say that something is lacking, be- cause the whole world has at times religious experience, and you must have lost it somewhere

if you don’t know what it is.

ou are not in a normal frame of mind. There is some trouble.

When that is the case, we know that some other type of psychological function is exaggerated through the ad- mixture of the energy which should normally be in a religious experience.

When you look at the life of a primitive tribe, as long as its religious life is well organized, things are in or- der.

Now let a missionary come in, who can sense nothing of primitive religions and simply says, "This is all wrong," and then you see how the religious life of the tribe begins to disintegrate.

This is one of the most extraordinary phenomena.

Then people become greedy, they become fresh; then a mission boy steps up to me and says, "I’m a brother

of yours, I’m just as good as you are, I know of those fellows Johnny, Marki, and Luki, all the bunch of them." That’s how they talk.

For years they sing a hymn in which there is a word meaning "hope," or "confidence."

A missionary who listened to that hymn didn’t know the accentuation of that word properly: If you put the accent on the last syllable it means "hope," and if you put it on the first, it means "locust."

So they sang, "Jesus is our locust," and that went quite well, because the locust is a religious figure in Africa.

So it meant something to them: "Jesus is a locust."

But it would have meant precious little to them to sing, "Jesus is our hope and confidence."

Even the highest people to whom I talked were quite unable to understand the elements of the Christian reli- gion.

How could they?

I have not found one mission boy in Africa who could have understood the elements of the Christian faith or what it is all about.

The Pueblo Indians told me, "Oh, it is very nice what the priest is doing; he comes along every second month, and when we bury our dead he does very interesting things with them, but then we do the Indian medicine afterwards."

You see, they always wrap up the dead twice, first according to the Christian rite and afterwards according to the Indian rite, and then it is finished.

The same with birth; in Indian families everything is done twice. I said, "That’s very nice, but do you know about Jesus?"

And they say, "Oh yes, we know about Jesu, and the priest often talks with a man he calls Jesu."

And I say, "What about the man?" and they say, "Oh, we don’t know; we don’t understand what he is all about."

And they are highly civilized people, philosophical people, even. The man who talked like that to me was a philosopher.

He was very critical, he had an excellent psychology.

He said, "Look at the white man’s face: sharp lines, disappointed nose; and these Americans are always seeking something.

We don’t know what they are seeking; we think they are all crazy." He made the right diagnosis!

Don’t be too triumphant; it isn’t only the Americans; it is the white man. And he felt it.

It was the first time I got a really objective line on the white man. I saw suddenly with his eyes. Such people understand nothing of the Christian religion, what it really is.

If you break up a tribe, they lose their religious ideas, the treasure of their old tradition, and they feel out of form completely.

They lose their raison d’etre, they grow hopeless.

That medicine man, with tears in his eyes, said, "We have no dreams any more." "Since when?" "Oh, since the British are in the country."

They are entirely depossessed, all the meaning goes out of their life; it does not make sense any more because we infect them with our insanity.

Because it is an insanity: we have lost the religious order of life.

That is my idea, and that is the point at which I will come to a conclusion. Carl Jung, C.G. Jung Speaking: Interviews and Encounters, Pages 99-113